Classes are done. (All but the grading.)

My conference on "Multilingual Jewish Literature and Multicultural America," down at the U of Chicago, is done. I got to respond to two dear friends, Maeera Shreiber and "Not That" Norman Finkelstein. ("Not that" meaning not the political-science professor late of DePaul University, most recently spotted mourning his martyrdom to big crowds at Princeton. My heart bleeds.)

The copyedited manuscript of

Ronald Johnson: Life and Works is now at the indexer. It will come out... I don't know. Soon. Sooner now than before it was off at the indexer, yes?

The galleys of my fat new essay on Latino and Latina poets are corrected and back at

Parnassus. Look for it in the next issue, along with Mark Scroggins on Ron Johnson.

I've read Cynthia Ozick's odious

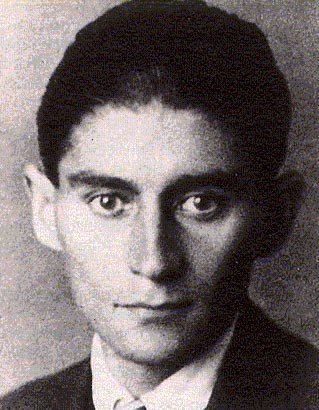

The Puttermesser Papers for the December Nextbook discussion group up at the Wilmette Public Library. Next week it's Kafka's

Metamorphosis, so I still need to work that up. I'd rather read

Kafka's Motorbike, the Greatest Novel of Our Time, but that's another blog post. Question: why does anyone like Cynthia Ozick's work? She's a masterful prose writer, but so what?

Puttermesser is as bleak, mean-spirited, and pessimistic as anything I've ever slogged through. I wanted to rinse my mouth out after I read it. I guess that means it's Important Literature. Feh.

I've finished my Institutional Compliance Training workshop. I solemnly swear to comply with my institution. Respect it? A little less, each year: not my colleagues or my students, but my administration.

Shrug. Compared to a law firm, DePaul is heaven on earth. Enough kvetching.

Got my first decent night's sleep last night in weeks. "Grant us sleep, thy most precious gift." Oh, wait, that was "grant us

peace" we used to say in Temple. Whatever. My dad was always asleep by that point, teaching me a noble lesson. I pass along lessons to my son, too. Last night it was a line from Ishmael Reed: "Son, neo-hoodoo never says no to pork."

My daughter and I sing Avril Lavigne songs together. "I hate it when a guy / doesn't get the door / even though I told him yesterday / and the day before..." "Sk8terboy" is a good song, with pronoun drama to die for. She's just a girl, I'm just an English professor--can I make it any more obvious?

***

I stumbled over to Josh Corey's website this morning and found a little kvetch from him, or at least a murmur of discontent, over what's been said about him over at the Poetry Foundation's

Harriet blog, which (unlike dear

Cahiers de Corey) I have trouble reading. Here's the young man in his own words:

In her most recent post at Harriet, the Poetry Foundation's blog, Ange Mlinko identifies me as belonging to a coterie of male poet-bloggers who have arrogated to themselves the privilege of deciding "what innovative is." It's interesting to be interpolated as a member of the patriarchy: it feels, and probably is, impersonal to who I actually am and what my real opinions might be (about feminism, for instance). That is, I doubt Ange intends any personal malice. But whether or not I fit the powdered wig she's placing on me, I have no doubt but that she's addressing a real and serious problem of underepresentation of women in a community with supposed egalitarian commitments.

The global frustration expressed by Ange (and by Julianna Spahr and Stephanie Young and others involved in the debate centering on the most recent issue of The Chicago Review) is one I've heard expressed locally by some of the women (and a few of the men) at the few poetry-related gatherings I've attended so far here in Chicago. That is, as far as the poetry scene here goes, it's a boys' town. I see no reason to doubt this assertion. Women are visible here, but the men are more so: a glance at The City Visible: Chicago Poetry for the New Century, as good an index of the State of the Post-Avant in the City of the Big Shoulders as any, shows me 21 women contributors out of 52 total, or 40 percent. Not exactly parity, is it? A similar, slightly wider disparity manifests when I compare how many of the poets included self-identify as editors, curators, or otherwise having a public platform that goes beyond just writing and teaching: 10 women to 16 men.

It seems self-evident to me that the work of feminism is far from over in any public sphere you'd care to name, including poetry; it's also clear that the avant-garde scene is no better (or worse) than the mainstream one when it comes to the patriarchal structure of power that is the default mode for all of our institutions. I'm talking about the real world relationships between people and the means of production, now—I am persuaded that the actual writing produced by the avant-garde has a greater potential to destabilize hierarchical structures of meaning and feeling than the mainstream epiphanic lyric does. But that only seems to apply to poems—the discourse around poetry, particularly in the reviled comments streams (mine are less populated than some but the number of female commenters seems much smaller than the male population), is masculinist by default when it isn't patently chauvinistic or violent (there's nasty stuff slung in Ron Silliman's comment fields almost every time a female poet is his subject).

Here's what I posted as a comment, in the hope that you'll comment here:

Dear Josh,

You write: "I am persuaded that the actual writing produced by the avant-garde has a greater potential to destabilize hierarchical structures of meaning and feeling than the mainstream epiphanic lyric does."

Here's my question. If the men who do and read this writing haven't been "destabilized" yet enough to change their ways, doesn't that call into question the idea that such work will have this effect? Sweet Virgin in the Fade, if it hasn't had that effect on Ron Silliman, who's made such verse his life, what makes us think it'll have that effect on anyone?

Conversely, I've seen oodles of anecdotal evidence (no empirical studies, mind you) of women's lives being changed, empowered, made better and happier, by reading precisely the least AG writing out there in the marketplace, my beloved popular romance fiction.

There are plenty of ways to defend the avant-garde, but as the years go by, I think the argument from efficacy ("a greater potential to destabilize hierarchical structures of meaning and feeling") gets weaker and weaker.

Here's my question to you, Dear Reader--and by now I think there is only one of you left!

How can anyone over, say, 40 still believe all this nonsense about poetry and politics?

I'm just

baffled, Dear Reader. I honestly don't understand how year after year, in the face of overwhelming evidence--the lack of any change in reader's lives or the culture at large or even (evidently) in this little subculture of the avant-garde--how anyone can still cling to this little myth about "destabilization." Even if you've seen change happen in your own classes, with your own students, surely that's the result of the pedagogy and not the poetry.

This isn't an article of faith for me. If you can point me to some evidence, I'd be grateful--although skeptical, yes, just as I am when people point me to the evidence that reading the Bible or the Book of Mormon or the Quran or the Diamond Sutra changes lives. But where is it? And if it ain't there, can't we please just drop this self-regarding, self-aggrandizing, ultimately narcissistic line of defense and find something new to say, for a change?