Teaching The Metamorphosis tonight. Well, not teaching it, exactly: talking about it with adult readers at the Wilmette Public Library, where I am leading discussions for a "Let's Talk About It: Jewish Literature" series sponsored by Nextbook.

My favorite book in the series so far has been S. Y. Ansky's play The Dybbuk, which is utterly wonderful; two books from now we'll do another play, Kushner's Angels in America, which I've taught a half-dozen times and love more the more I read it.

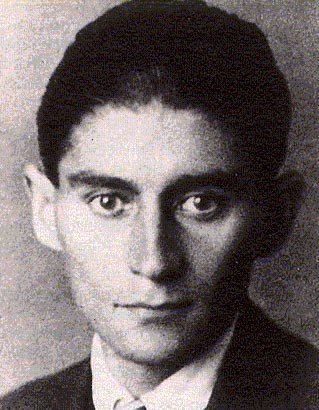

Kafka? Meh. Not a writer I love. I'm too optimistic, too happy, too American (perhaps) to feel that way, although I did my best to love him at 16 and 17. (Never could pull off that broody, angsty thing.) Still, he's not a writer I actively dislike, either, and I am actually rather proud of the take-home questions we handed out last month to prepare for tonight.

I'm off to reread the text itself--not much of the criticism satisfies me just now, so let me pass those questions along and pat myself on the back for posting something today.

Here they are: steal at will!

1) Unlike the first two books in this series, Satan in Goray and The Dybbuk, Kafka’s Metamorphosis does not explicitly deal with Jewish characters or Jewish subjects. What might be gained or lost by reading the book as a Jewish novel? How does it seem different if we read it this way, rather than as a Modernist or Central European text?

2) Readers who approach The Metamorphosis as a Jewish book often refer to one or both of the following passages from Kafka’s letters:

“Most young Jews who began to write German wanted to leave Jewishness behind them, and their fathers approved of this, but vaguely (this vagueness was what was so outrageous to them). But with their posterior legs they were still glued to their fathers' Jewishness and with their waving anterior legs they found no new ground. The ensuing despair became their inspiration. . . . The product of their despair became their inspiration. . . . The product of their despair could not be German literature, though outwardly it seemed to be so. They existed among three impossibilities, which I just happen to call linguistic impossibilities. . . . These are: the impossibility of not writing, the impossibility of writing German, the impossibility of writing differently. One might also add a fourth impossibility, the impossibility of writing. . . . “

"The disgusting shame of perennially living under protection. Is it not self-evident that one should leave where one is hated so much? (Zionism or ethnic feeling is not even needed here.) The heroism of staying under these conditions is that of cockroaches in the bathroom one cannot get rid of.”

3) Historian Gershom Scholem once wrote his friend Walter Benjamin that “I advise you to begin any inquiry into Kafka with the Book of Job, or at least with a discussion of the possibility of divine judgment, which I regard as the sole subject of Kafka’s production.” Benjamin took a different view, and wrote that “the most essential point about Kafka is his humor…. I believe someone who tried to see the humorous side of Jewish theology would have the key to Kafka.” Do either of these suggestions help us read The Metamorphosis? Is there any way to understand the book as concerned with divine judgment? Is it theological in a particularly Jewish or humorous way?

4) The Metamorphosis begins with Gregor’s transformation, and ends with a focus on his sister Grete. How does Kafka’s portrayal of Grete compare with Singer’s and Ansky’s treatment of female characters in Satan in Goray and The Dybbuk? Why might the novel end with a focus on her, rather than on her brother?

No comments:

Post a Comment