Like any sensible poetry teacher, I love to teach John Donne. Donne makes me look smart; all I have to do is paraphrase the poem well and accurately, and the students are impressed--by the poet, but also by

me. Just by knowing pretty basic stuff--say, what "dross" is, or an "alloy"--or by navigating through a complex, multiply-figured, multiply-subordinated sentence, I get to come across like some sort of trained professional. What's not to like?

Every now and then, however, teaching Donne gets

really fun, because it lets me joust with my colleagues. Last night, for example, I got into a lively debate with P-- over this little number from the Holy Sonnets:

Batter my heart, three-person'd God, for you

As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend;

That I may rise and stand, o'erthrow me, and bend

Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new.

I, like an usurp'd town to'another due,

Labor to'admit you, but oh, to no end;

Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend,

But is captiv'd, and proves weak or untrue.

Yet dearly'I love you, and would be lov'd fain,

But am betroth'd unto your enemy;

Divorce me,'untie or break that knot again,

Take me to you, imprison me, for I,

Except you'enthrall me, never shall be free,

Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

Says I to my colleague, those last two verbs are brilliant ("Brilliant!"--as in the Guinness ad) because of the way they take Donne from the violent verbs he starts with into an aesthetic realm, a realm of transport, of delight. To be

enthralled doesn't just literally mean to be imprisoned, says I; you can be enthralled by a plot, by an argument, but a poem. To be

ravished doesn't mean to be raped (although my students have been taught so); it's a broader, less brutal, more delightful thing. In fact, says I, what Donne wants by the end of the poem is for God to

out-Donne him, to do unto the poet what the poet does to us. "Batter my heart" doesn't batter or break us, but it does enthrall and ravish us. Says I.

Says P--, a Renaissance scholar, "I bet those words didn't have those meanings in Donne's time." "You're on," says I, and off we trot to the OED, one dollar hanging in the balance. (Don't scoff: that's four shots of in-house espresso from the Modern Languages department.

Ladies and Gentlemen, the envelope, please:

Enthrall:

1. trans. To reduce to the condition of a thrall; to hold in thrall; to enslave, bring into bondage. Now rare in lit. sense.

1656 COWLEY Pindar. Odes, Brutus iii, Ingrateful Cæsar who could Rome enthrall. 1659 PEARSON Creed (1839) 512 A ransom is..that which is detained, or given for the releasing of that which is enthralled. 1777 WATSON Philip II (1839) 321 The danger..of being again enthralled by the Spaniards. 1871 B. TAYLOR Faust (1875) I. xxv, I am free! No one shall enthrall me.

1656 COWLEY Pindar. Odes, Brutus iii, Ingrateful Cæsar who could Rome enthrall. 1659 PEARSON Creed (1839) 512 A ransom is..that which is detained, or given for the releasing of that which is enthralled. 1777 WATSON Philip II (1839) 321 The danger..of being again enthralled by the Spaniards. 1871 B. TAYLOR Faust (1875) I. xxv, I am free! No one shall enthrall me.

1614 RALEIGH Hist. World I. 39 Those people, which he [the Turk] hath subjected and inthralled. 1636 E. DACRES tr. Machiavel's Disc. Livy II. 495 It is as hard and dangerous..to inthrall a people, that would live free.

1614 RALEIGH Hist. World I. 39 Those people, which he [the Turk] hath subjected and inthralled. 1636 E. DACRES tr. Machiavel's Disc. Livy II. 495 It is as hard and dangerous..to inthrall a people, that would live free.

2. fig. To ‘enslave’ mentally or morally. Now chiefly, to captivate, hold spellbound, by pleasing qualities.

1576 NEWTON tr. Lemnie's Complex. (1633) 170 A man should not give over or enthrall his credit and honour to Harlots. 1590SHAKES. Mids. N. III. i. 142 So is mine eye enthralled to thy shape. 1695 LD. PRESTON Boeth. IV. 177 Vice doth enthral Men's strongest Powers. 1797 MRS. RADCLIFFE Italian xvii, He was inclined to believe that a stratagem had enthralled him. a1839 PRAED Poems (1864) II. 123 And M

1576 NEWTON tr. Lemnie's Complex. (1633) 170 A man should not give over or enthrall his credit and honour to Harlots. 1590SHAKES. Mids. N. III. i. 142 So is mine eye enthralled to thy shape. 1695 LD. PRESTON Boeth. IV. 177 Vice doth enthral Men's strongest Powers. 1797 MRS. RADCLIFFE Italian xvii, He was inclined to believe that a stratagem had enthralled him. a1839 PRAED Poems (1864) II. 123 And M , in that simple dress, Enthralls us more by studying less. 1878 E. JENKINS Haverholme 136 He was enthralled by the wizard spell of the orator.

, in that simple dress, Enthralls us more by studying less. 1878 E. JENKINS Haverholme 136 He was enthralled by the wizard spell of the orator.

1603 DANIEL Def. Rhime (1717) 12 Seeking to please our Ear, we inthral our Judgment. 1636 HEALEY Theophrast., Impert. Diligence 53 This fellow perswades him not so much to inthrall himselfe to his Physicians directions. c1720 PRIOR Poems (1866) 12 She soothes, but never can inthral my mind. a1803 BEATTIE Hermit (R.), Spring shall return, and a lover bestow And sorrow no longer thy bosom enthrall. 1859KINGSLEY Raleigh Misc. I. 30 The sense of beauty inthralls him at every step. 1876 BANCROFT Hist. U.S. I. xviii. 516 To inthrall his mind by the influences of religion.

1603 DANIEL Def. Rhime (1717) 12 Seeking to please our Ear, we inthral our Judgment. 1636 HEALEY Theophrast., Impert. Diligence 53 This fellow perswades him not so much to inthrall himselfe to his Physicians directions. c1720 PRIOR Poems (1866) 12 She soothes, but never can inthral my mind. a1803 BEATTIE Hermit (R.), Spring shall return, and a lover bestow And sorrow no longer thy bosom enthrall. 1859KINGSLEY Raleigh Misc. I. 30 The sense of beauty inthralls him at every step. 1876 BANCROFT Hist. U.S. I. xviii. 516 To inthrall his mind by the influences of religion.

Hence en thralled ppl. a. enthraller, one who enthralls. en

thralled ppl. a. enthraller, one who enthralls. en thrallingvbl. n. and ppl. a.

thrallingvbl. n. and ppl. a.

1591 SHAKES. Two Gent. II. iv. 134 Loue hath chas'd sleepe from my enthralled eyes. 1600 HOLLAND Livy II. xxiv. 59 The enthralled debtors..were immediatlie by name enrolled. 1644MILTON Areop. (Arb.) 75 Through our..backwardnes to recover any enthrall'd peece of truth out of the gripe of custom. 1640-4 in Rushw. Hist. Coll. 111 (1692) I. 93 The subjecting and inthralling all Ministers under them. 1669COKAINE Poems 149 Her sweetest mouth..[is] All hearts enthraller. 1797 BURKE Regic. Peace iii. Wks. VIII. 311 With an enthralled world to labour for them. 1820 SCOTT Monast. xiii, Those of the Sucken, or enthralled ground, were liable in penalties. 1871MACDUFF Mem. Patmos xiv. 195 To break loose from the enthralling chains of earth.

Ravish (note meaning 3 a, b, and c)

[a. F. raviss-, lengthened stem of ravir to seize, take away: pop. L. *rap

pop. L. *rap re, class. L. rap

re, class. L. rap re. Cf. RAVIN1.]

re. Cf. RAVIN1.]

1. a. trans. To seize and carry off (a person); to take by violence, to tear or drag away from (a place or person). Now somewhat rare.  Also, to sweep or carry away; to drag off (to or into a place). Obs.

Also, to sweep or carry away; to drag off (to or into a place). Obs.

a1300 Cursor M. 7680 His reners [saul]  eder send For to rauis dauid he wend. a1340 HAMPOLE Psalter lxii. 8, I am thi bridde & if

eder send For to rauis dauid he wend. a1340 HAMPOLE Psalter lxii. 8, I am thi bridde & if  ou hill me not

ou hill me not  e glede will ravishe me. 1422 tr. Secreta Secret., Priv. Priv. 174 The course of the ryuer so stronge and so styfe rane, that the knyght and his hors rauyshith, doune hym bare, and dreynte. 1585 T. WASHINGTON tr. Nicholay's Voy. III. i. 69 [They] by outragious force rauish these most deare infants..from..their fathers and mothers. 1603 B. JONSON Sejanus V. x, Now inhumanely ravish him to Prison! 1624 QUARLES Sion's Elegies iv. 20 Heaven's Anoynted, Their hands have crusht, and ravisht from his Throne. 1655FULLER Ch. Hist. I. v. §20 The British are not so over-fond of St. Patrick, as to ravish him into their Country against his will, and the consent of Time. 1854 SUMNER Speech in Wks. 1895 III. 291 For the mother there is no assurance that her infant child will not be ravished from her breast.

e glede will ravishe me. 1422 tr. Secreta Secret., Priv. Priv. 174 The course of the ryuer so stronge and so styfe rane, that the knyght and his hors rauyshith, doune hym bare, and dreynte. 1585 T. WASHINGTON tr. Nicholay's Voy. III. i. 69 [They] by outragious force rauish these most deare infants..from..their fathers and mothers. 1603 B. JONSON Sejanus V. x, Now inhumanely ravish him to Prison! 1624 QUARLES Sion's Elegies iv. 20 Heaven's Anoynted, Their hands have crusht, and ravisht from his Throne. 1655FULLER Ch. Hist. I. v. §20 The British are not so over-fond of St. Patrick, as to ravish him into their Country against his will, and the consent of Time. 1854 SUMNER Speech in Wks. 1895 III. 291 For the mother there is no assurance that her infant child will not be ravished from her breast.

fig. 1513 DOUGLAS Æneis VIII. i. 49 In mynd..Nou heyr, nou there, revist in syndry partis. 1560 J. DAUS tr. Sleidane's Comm. 464b, Many men rauished & toste hither and thither with euery wynde of doctrine.

b. In pass.: To be carried away from a belief, state, etc. Obs.

b. In pass.: To be carried away from a belief, state, etc. Obs.

1362 LANGL. P. Pl. A. XI. 297 Arn none rathere yrauisshid fro the ri t beleue Thanne arn thise grete clerkis. a1400-50 Alexander 4424

t beleue Thanne arn thise grete clerkis. a1400-50 Alexander 4424  us fra

us fra  e rote of ri

e rote of ri twisnes rauyst ere

twisnes rauyst ere  e clene. c1425 Found. St. Bartholomew's (E.E.T.S.) 45 In his slepe he was raueshid from his resonable wyttys. 1758 H. WALPOLE Catal. Roy. Authors (1759) I. 157 Ravished from all improvement and reflection at the age of seventeen.

e clene. c1425 Found. St. Bartholomew's (E.E.T.S.) 45 In his slepe he was raueshid from his resonable wyttys. 1758 H. WALPOLE Catal. Roy. Authors (1759) I. 157 Ravished from all improvement and reflection at the age of seventeen.

c. To draw forcibly to (or into) some condition, action, etc. Obs.

c. To draw forcibly to (or into) some condition, action, etc. Obs.

1398 TREVISA Barth. De. P.R. II. iv. (1495) bijb/2 Aungels ben..rauysshed to the Innest contemplacion of the loue of god. 1450-1530 Myrr. our Ladye 329 That whyle we know god vysybly, by hym we mote be rauyshed in to the loue of inuysyble thynges. 1574 tr. Marlorat's Apocalips 23 Christes works..might rauish all men to haue them in wonderfull admiration. 1600HOLLAND Livy X. xli. 382 The Romanes were ravished and carried on end to the battaile, with anger, hope, and heate of conflict.

2. a. To carry away (a woman) by force. (Sometimes implying subsequent violation.) Also said fig. of death. ? Obs.

a1300 Cursor M. 7048 Alexandre, in  at siquar,

at siquar,  at paris hight, raiuist helayn. 1303 R. BRUNNE Handl. Synne 7422

at paris hight, raiuist helayn. 1303 R. BRUNNE Handl. Synne 7422  ay rauys a mayden a

ay rauys a mayden a ens here wyl, And mennys wyuys

ens here wyl, And mennys wyuys  ey lede awey

ey lede awey  ertyl. 1387TREVISA Higden (Rolls) I. 171 Iupiter..rauisched Europa, Agenores dou

ertyl. 1387TREVISA Higden (Rolls) I. 171 Iupiter..rauisched Europa, Agenores dou ter. c1477 CAXTON Jason 8 They rauisshed the fayr Ypodame out from alle the other ladyes. 1585 T. WASHINGTON tr. Nicholay's Voy. II. iii. 33 It was there..Paris after he had rauished Helene, tooke of her the first frutes of his loue. c1665 MRS. HUTCHINSON Mem. Col. Hutchinson (1846) 49 Death quenched the flame and ravished the young lady from him.

ter. c1477 CAXTON Jason 8 They rauisshed the fayr Ypodame out from alle the other ladyes. 1585 T. WASHINGTON tr. Nicholay's Voy. II. iii. 33 It was there..Paris after he had rauished Helene, tooke of her the first frutes of his loue. c1665 MRS. HUTCHINSON Mem. Col. Hutchinson (1846) 49 Death quenched the flame and ravished the young lady from him.

b. To commit rape upon (a woman), to violate. Also absol.

1436 Rolls of Parlt. IV. 498/1 [He] flesshly knewe and ravysshed ye said Isabell. 1560 J. DAUS tr. Sleidane's Comm. 220b, The women and maides that were fled thither for feare, they ravissh every one [L. constuprant]. 1642FULLER Holy & Prof. St. V. xi. 397 Defiling virgins, or ravishing them rather, for consent onely defiles. 1756-7 tr. Keysler's Trav. (1760) II. 159 The Locis Turpitudinis, as it is called, where St. Agnes was in danger of being ravished by two soldiers. 1834 Cycl. Pract. Med. III. 583/1 Ravishing by force any woman-child..or any other woman. 1939 G. B. SHAW Geneva III. 70 Am I to allow him to kill me and ravish my wife and daughters? 1981 Sunday Times (Colour Suppl.) 8 Mar. 104 He ravished and pillaged...left sons to hate him, women to fight over his wealth.

fig. 1664 DRYDEN Rival Ladies II. i, Against her Will fair Julia to possess, Is not t'enjoy but ravish Happiness. 1782 COWPER Table T. 332 May no foes ravish thee [Liberty], and no false friend Betray thee, while professing to defend.

c. To spoil, corrupt. Obs. rare

c. To spoil, corrupt. Obs. rare 1.

1.

1593 SHAKES. Lucr. 778 O hateful, vaporous, and foggy Night..With rotten damps ravish the morning air.

3. a. To carry away or remove from earth (esp. to heaven) or from sight. Now rare.

a1300 Cursor M. 18483 We sal be rauist forth a-wai, Sal na man se us fra  at dai. 1340 HAMPOLE Pr. Consc. 5050 We..Sal

at dai. 1340 HAMPOLE Pr. Consc. 5050 We..Sal  an with

an with  am in cloudes be ravyste Up in-to

am in cloudes be ravyste Up in-to  e ayre. c1375 Sc. Leg. Saints x. (Matthew) 210 It hapnyt

e ayre. c1375 Sc. Leg. Saints x. (Matthew) 210 It hapnyt  e kingis son be ded..

e kingis son be ded.. ai tald

ai tald  e kynge

e kynge  at goddis had rawist hyme. c1450 LYDG. & BURGH Secrees 97 He was Ravysshed Contemplatyff of desir Vp to the hevene lyk a dowe of ffyr. 1513DOUGLAS Æneis I. i. 50 Ganimedes reveist aboue the sky. 1697 DRYDEN Virg. Georg. IV. 719 For ever I am ravish'd from thy sight. 1754 FIELDING Jonathan Wild IV. vii, A very thick mist ravished her from our eyes. 1885-94 R. BRIDGESEros & Psyche Oct. xii, Ravisht to hell by fierce Agesilas, Thou soughtest her on earth and couldst not find.

at goddis had rawist hyme. c1450 LYDG. & BURGH Secrees 97 He was Ravysshed Contemplatyff of desir Vp to the hevene lyk a dowe of ffyr. 1513DOUGLAS Æneis I. i. 50 Ganimedes reveist aboue the sky. 1697 DRYDEN Virg. Georg. IV. 719 For ever I am ravish'd from thy sight. 1754 FIELDING Jonathan Wild IV. vii, A very thick mist ravished her from our eyes. 1885-94 R. BRIDGESEros & Psyche Oct. xii, Ravisht to hell by fierce Agesilas, Thou soughtest her on earth and couldst not find.

b. To carry away (esp. to heaven) in mystical sense; to transport in spirit without bodily removal.

c1330 Arth. & Merl. 8915 (Kölbing) This Naciens..Whom se

en

en  e holi godes gras Rauist in to

e holi godes gras Rauist in to  e

e  ridde heuen, Where he herd angels steuen. c1400MANDEVILLE (Roxb.) xxvi. 124

ridde heuen, Where he herd angels steuen. c1400MANDEVILLE (Roxb.) xxvi. 124  anne

anne  ei seyn

ei seyn  at he is ravissht in to ano

at he is ravissht in to ano er world. 1482 Monk of Evesham (Arb.) 36 Y was rauyshte in spirite as y laye in the chaptur hows. 1552LYNDESAY Monarche 6076 Quhen Paull wes reuyst, in the spreit, Tyll the thrid Heuin. 1615 G. SANDYS Trav. 56 They haue..naturall idiots, in high veneration; as men rauished in spirit, and taken from themselues, as it were, to the fellowship of Angels. 1644 EVELYNMem. (1857) I. 117 It has some rare statues, as Paul ravished into the third heaven.

er world. 1482 Monk of Evesham (Arb.) 36 Y was rauyshte in spirite as y laye in the chaptur hows. 1552LYNDESAY Monarche 6076 Quhen Paull wes reuyst, in the spreit, Tyll the thrid Heuin. 1615 G. SANDYS Trav. 56 They haue..naturall idiots, in high veneration; as men rauished in spirit, and taken from themselues, as it were, to the fellowship of Angels. 1644 EVELYNMem. (1857) I. 117 It has some rare statues, as Paul ravished into the third heaven.

c. To transport with the strength of some feeling, to carry away with rapture; to fill with ecstasy or delight; to entrance. Also const. from.

13.. E.E. Allit. P. A. 1087 So was I rauyste wyth glymme pure. 1377LANGL. P. Pl. B. II. 17 Hire arraye me rauysshed, sucche ricchesse saw I neuere. 1484 CAXTON Fables of Alfonce i, The medecyns..sayd that..he was rauysshed by loue. a1533 LD. BERNERS Huon cxliv. 538 She had suche ioye that of a great spase she coude speke no word, she was so rauysshyd. 1586 A. DAY Eng. Secretary (1625) 23 Doth not the learned Cosmographie..rauish vs oftentimes and bring in contempt the pleasures of our owne soyle. 1695BLACKMORE Pr. Arth. II. 316 Ambrosial Juices, sweet Nectarean Wine, Ravish'd their Tast. 1753 HOGARTH Anal. Beauty v. 28 Ravish the eye with the pleasure of the pursuit. 1826 E. IRVING Babylon II. VIII. 282, I have been wrapt in wonder, and ravished with delight, in the study of it. 1873BROWNING Red Cotton Night-Cap Country IV. 135 You ravish men away From puny aches and petty pains.

4. a. To seize and take away as plunder or spoil; to seize upon (a thing) by force or violence; to make a prey of.  Also with away.

Also with away.

c1374 CHAUCER Boeth. IV. pr. v. 102 (Camb. MS.) Shrewes rauysshen medes of vertu and ben in honours and in gret estatis. 1382WYCLIF Nahum ii. 9 Rauyshe  e syluer, rauyshe

e syluer, rauyshe  e gold. 1483 CAXTON Cato Biij, To be wyllyng for to dyspoyle and rauysshe hys neyghbours goodes. 1535 COVERDALE Gen.a1661 FULLERWorthies (1840) II. 104 Some antiquaries are so jealous of their works, as if every hand which toucheth would ravish them. 1731 MEDLEY Kolben's Cape G. Hope l. 66 The Free-booters had used to ravish away their lives and their cattle. 1794 BURKE Sp. agst. W. Hastings Wks. 1826 XV. 430 To steal an iniquitous judgment, which you dare not boldly ravish. xxxvii. 33 A rauyshinge beast hath rauyshed Ioseph.

e gold. 1483 CAXTON Cato Biij, To be wyllyng for to dyspoyle and rauysshe hys neyghbours goodes. 1535 COVERDALE Gen.a1661 FULLERWorthies (1840) II. 104 Some antiquaries are so jealous of their works, as if every hand which toucheth would ravish them. 1731 MEDLEY Kolben's Cape G. Hope l. 66 The Free-booters had used to ravish away their lives and their cattle. 1794 BURKE Sp. agst. W. Hastings Wks. 1826 XV. 430 To steal an iniquitous judgment, which you dare not boldly ravish. xxxvii. 33 A rauyshinge beast hath rauyshed Ioseph.

absol. 1712-14 POPE Rape Lock II. 32 He meditates the way, By force to ravish, or by fraud betray.

fig. c1374 CHAUCER Boeth. III. pr. i. 50 (Camb. MS.) Whan  at thow ententyf and stylle rauysshedest my wordes.

at thow ententyf and stylle rauysshedest my wordes.

b. To carry, take, pull, or drag away or along in a violent manner without appropriation; to remove by force. Also with away, down. Obs.

b. To carry, take, pull, or drag away or along in a violent manner without appropriation; to remove by force. Also with away, down. Obs.

c1374 [see RAVISHING ppl. a. 1]. 1398TREVISA Barth. De P.R. VIII. xxii. (Bodl. MS.) lf. 86/1 Aboute  e whiche axis alle

e whiche axis alle  e swiftenes of

e swiftenes of  e firmament is rauessched and ymeued. 1460-4 Paston Lett. No. 434 II. 81 The gret fray..ravyched my witts and mad me ful hevyly dysposyd. 1535 COVERDALE Prov. i. 12 These are the ways of all soch as be couetous, that one wolde rauysh anothers life. 1620 MELTON Astrolog. 65 His minde was rauished downe the swift torrent of an insolent vanity. 1698 CROWNE Caligula III, Rivers he ravishes, and turns their courses!

e firmament is rauessched and ymeued. 1460-4 Paston Lett. No. 434 II. 81 The gret fray..ravyched my witts and mad me ful hevyly dysposyd. 1535 COVERDALE Prov. i. 12 These are the ways of all soch as be couetous, that one wolde rauysh anothers life. 1620 MELTON Astrolog. 65 His minde was rauished downe the swift torrent of an insolent vanity. 1698 CROWNE Caligula III, Rivers he ravishes, and turns their courses!

c. Const. from, out of,  into, to.

into, to.

1398 TREVISA Barth. De P.R. XVI. vii. (Bodl. MS.),  if

if  ow doste

ow doste  er on [on quicksilver] a scrupil of golde it rauessche

er on [on quicksilver] a scrupil of golde it rauessche into it silfe

into it silfe  e li

e li tnes

tnes  erof. c1400 Rom. Rose 5198, I mene not that [love] which makith thee wood,..And ravysshith fro thee all thi witte. 1563 WIN

erof. c1400 Rom. Rose 5198, I mene not that [love] which makith thee wood,..And ravysshith fro thee all thi witte. 1563 WIN IT Wks. (1890) II. 16 We also.. suld reuiss fra it, that mot proffet to the lyfe eternall. 1634 W. TIRWHYT tr. Balzac's Lett.1722DE FOE Col. Jack (1840) 175, I..am not..obliged to ravish my bread out of the mouths of others. 1748 RICHARDSON Clarissa1838 PRESCOTT Ferd. & Is. (1846) I. ii. 135 The crown was ravished from her posterity. 1871 R. ELLIS Catullus lxiv. 5 Fain from Colchian earth her fleece of glory to ravish. (vol. I.) aij, The onely thing hee supposed to possess..was ravished from him. (1811) II. xxxiii. 239 He even snatched..my struggling hand; and ravished it to his odious mouth.

IT Wks. (1890) II. 16 We also.. suld reuiss fra it, that mot proffet to the lyfe eternall. 1634 W. TIRWHYT tr. Balzac's Lett.1722DE FOE Col. Jack (1840) 175, I..am not..obliged to ravish my bread out of the mouths of others. 1748 RICHARDSON Clarissa1838 PRESCOTT Ferd. & Is. (1846) I. ii. 135 The crown was ravished from her posterity. 1871 R. ELLIS Catullus lxiv. 5 Fain from Colchian earth her fleece of glory to ravish. (vol. I.) aij, The onely thing hee supposed to possess..was ravished from him. (1811) II. xxxiii. 239 He even snatched..my struggling hand; and ravished it to his odious mouth.

d. With double object. Obs.

d. With double object. Obs.

c1400 Destr. Troy 462 The sight of  at semely..rauysshed hir radly

at semely..rauysshed hir radly  e rest of hir sawle. a1500 Sir Beues 3917 (Pynson) Thou haste rauysshed my men theire liffe.

e rest of hir sawle. a1500 Sir Beues 3917 (Pynson) Thou haste rauysshed my men theire liffe.

5. a. To ravage, despoil, plunder. Obs.

5. a. To ravage, despoil, plunder. Obs.

1297 R. GLOUC. (Rolls) 4001  ou..rauissest france & o

ou..rauissest france & o er londes. a1340 HAMPOLE Psalter ix. 32 He waites

er londes. a1340 HAMPOLE Psalter ix. 32 He waites  at he rauysch

at he rauysch  e pore. 1388 WYCLIF Isa. xlii. 22 Thilke puple was rauyschid and wasted. c1619 BACON Sp. concerning War w. Spain Rem. (1734) 226 We ravished a principal City of wealth and strength.

e pore. 1388 WYCLIF Isa. xlii. 22 Thilke puple was rauyschid and wasted. c1619 BACON Sp. concerning War w. Spain Rem. (1734) 226 We ravished a principal City of wealth and strength.

b. To despoil, rob, or deprive (one) of something. Obs.

b. To despoil, rob, or deprive (one) of something. Obs.

1362 LANGL. P. Pl. A. IV. 34 And hou he rauischede Rose, Reynaldes lemmon, And Mergrete of hire maydenhod. 1560 J. DAUS tr. Sleidane's Comm. 29b, I am not led rashely on like one that were ravished of his wittes. 1606 G. W[OODCOCKE] Hist. Ivstine VIII. 38 Assailing the brothers..[he] rauisht them both of their kingdomes. 1686 F. SPENCE tr. Varilla's Ho. Medicis 240 As he was..more methodick than Blondus, he ravish'd him of his reputation. a1803 Hughie GrameBallads IV. 13 They may ravish me o' my life, But they canna banish me fro Heaven hie. xiv. in Child

Eccovi! Judge ye! Who gets the coffee next week?

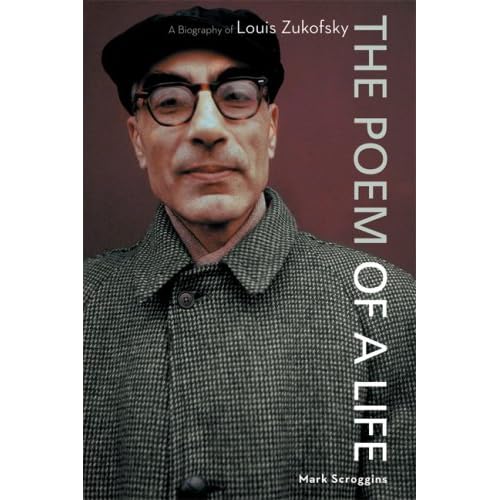

Sweet words this morning from Mark, mon semblable, mon frere, concerning my burst of mid-life, mid-career angst. "I've always felt like Jack Lemmon to his Tony Curtis," says he; that would be me on the left, then, the brunette. For the record, I've always thought of Mark as the real scholar in our little fellowship: the one who's done the legwork, mulled things over, and who therefore speaks with authority. I'm good for a flip word, a sprightly opinion, and every now and then a valiant effort, but I"m as often comic relief as intellectual protagonist. Pippin to his Frodo, say, or Buffy to his Giles.

Sweet words this morning from Mark, mon semblable, mon frere, concerning my burst of mid-life, mid-career angst. "I've always felt like Jack Lemmon to his Tony Curtis," says he; that would be me on the left, then, the brunette. For the record, I've always thought of Mark as the real scholar in our little fellowship: the one who's done the legwork, mulled things over, and who therefore speaks with authority. I'm good for a flip word, a sprightly opinion, and every now and then a valiant effort, but I"m as often comic relief as intellectual protagonist. Pippin to his Frodo, say, or Buffy to his Giles.